Since the publication of The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins I have received many emails asking me to clarify facts about the life of Sir Hubert Wilkins, because other recent books give different versions of what happened. I wrote the article Sir Hubert Wilkins: Sorting Fact from Fiction to explain why Wilkins wrote different versions of his life. But one story that still has people asking questions, or wanting clarification, relates to the aeroplane that Wilkins sold to pioneer Australian aviator Sir Charles Kingsford Smith. It became Australia’s most famous aeroplane after Kingsford Smith renamed it Southern Cross and, along with Charles Ulm, flew it across the Pacific Ocean in 1928. There are many stories still being published today that claim the Southern Cross was a hybrid plane, made from the wing of one Fokker, and the fuselage of another.

In The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, aviation enthusiasts saw that I had discovered and published the original specification sheet of the three engine Fokker used by Wilkins, so I received a number of enquiries asking me explain the origins of the Southern Cross.

To explain, we firstly need to see how the idea that the Southern Cross was a composite plane originated, and for this we turn to Sir Charles Kingsford Smith himself. In 1932, Kingsford Smith published The Old Bus (sometimes titled The Southern Cross Story) about his famous aeroplane. In the book, Kingsford Smith describes meeting Sir Hubert Wilkins and purchasing the plane from him. Kingsford Smith talks about Wilkins having two Fokkers, one of which had already been damaged. When Wilkins crashed the second Fokker, he repaired it with parts from the damaged one. Kingsford Smith writes: “In the reconstruction Wilkins had accidentally improvised a new type of plane by using the good wing of the F7 with the singled-motored fuselage of the other, the wing of which had been damaged.” The idea that the Southern Cross was a special plane, created by accident from improvised parts is romantic, and made a better story than the truth. As a consequence, the story has come to be told and retold many times, without people actually knowing what happened.

So, in this article, I would like to explain the story and show the photographs of the various versions of the Fokkers that Sir Hubert Wilkins had in 1926 and 1927, and reveal truth behind the plane that became Kingsford Smith’s Southern Cross.

In 1926, Wilkins was being sponsored to explore the Arctic by a businessmen from Detroit, Michigan. He bought two planes from Dutch manufacturer, Anthony Fokker, who had recently set up a factory in New Jersey, USA, because he was trying to expand his market in America. Fokker saw a future for aviation in passenger services.

Fokker also believed that, for passenger services, three engine planes would be safer, because if one engine failed, the plane could still fly on the other two. So, using the same fundamental fuselage, he built an F VII with a wider wing. Beneath the wing he slung two Wright Whirlwind air-cooled radial engines. The third engine, at the nose of the fuselage, was also a Wright Whirlwind. The specification sheet that I located is for the three engine plane. Wilkins has written across the bottom, “This is the type of airplane that I will have but mine will be a bit larger than this one.”

There’s a few interesting things about this spec sheet, which is really a kind of sales brochure. Fokker talks about the importance of added safety and carrying capacity, especially for passenger flights. He explains how taking the single engine Fokker FVII, and making it a three engine plane, gave it longer range, and safety because if one engine stopped, it could still be flown using the remaining two. He also says on the spec sheet, “the radial air-cooled engines have a further great commercial advantage in their accessibility, quick removability and easy replacement of major parts”.

So in 1926, Wilkins bought two of these planes. With both planes disassembled and crated at Fokker’s New Jersey factory, Sir Hubert Wilkins had them taken across America by train to Seattle on the West Coast. From there they were put aboard a ship, and taken north to Seward, Alaska. At Seward, they were put back on a train and taken north as far north as the rail line went, which was Fairbanks. At Fairbanks, both planes were assembled. They were also christened and the name of the expedition was painted on the side. The single engine plane was called the ‘Alaskan’. The three-engine plane was called the ‘Detroiter’, because of the sponsorship of the Detroit businessmen. On the sides of both planes were painted the words ‘Detroit Arctic Expedition’.

At this point things started to go badly wrong. First the three engine plane was crashed, damaging the front mounting and engine, but not the wing.

While it was being repaired, Wilkins made a number of flights in the single engine Alaskan from Fairbanks, north over the Endicott Mountains, to Barrow on the north coast of Alaska.

On one of his flights to Barrow, he crashed the single engine Alaskan and broke the wing. It could not be repaired. The crashes and other setbacks meant that Sir Hubert Wilkins was able to stockpile fuel at Barrow, but he was not able make any flights over the Arctic Ocean before the summer season ended. He stored the fuselage of the Alaskan single engine plane, and the complete three engine Detroiter at Fairbanks, and returned to Detroit to face his disgruntled sponsors. The Detroit businessmen decided not to continue their sponsorship.

After so many crashes taking off and landing on rough icy runways, he wanted planes that could take off and land in a shorter distance. Both the Alaskan and the Detroiter had used wheels, and Wilkins believed this had also contributed to their crashes.

He purchased two Stinson biplanes. They were smaller and lighter, and Wilkins thought they would be more suitable for Arctic conditions than the large heavy Fokkers. The Stinson biplanes were shipped to Fairbanks Alaska in March 1927 and Wilkins was ready to try again. It’s important at this point to understand that the name of the expedition had changed. In 1926, it had been the Detroit Arctic Expedition.

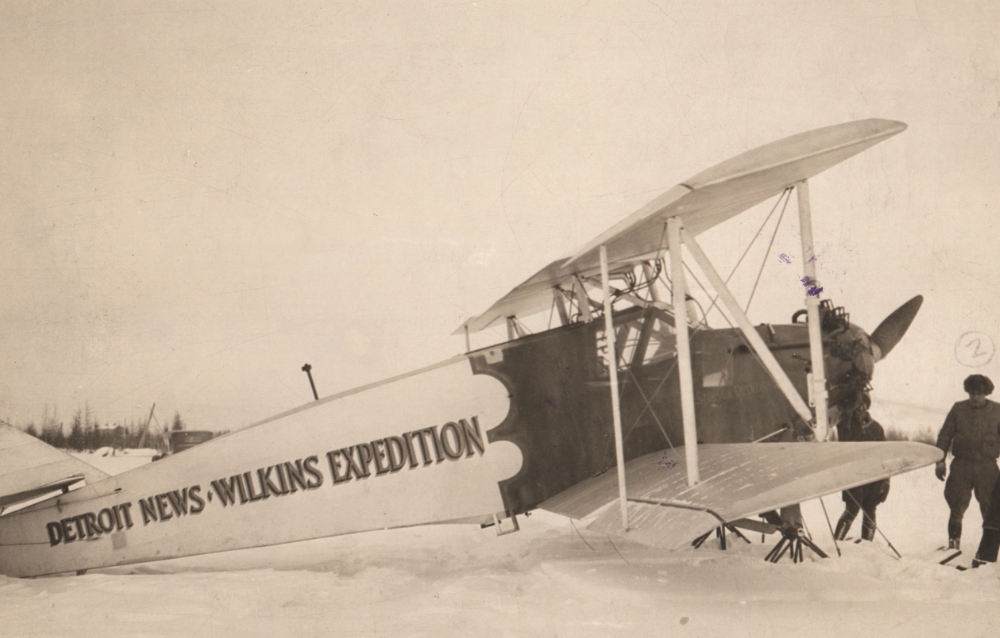

In 1927 the Detroit businessmen had stopped their sponsorship, but Wilkins was still being sponsored by the Detroit News newspaper. So for 1927 the name of the expedition was changed to the Detroit News Expedition. That name was painted on the side of the Stinsons. The smaller Stinsons might be more suited for flying over the rough Arctic ice, but they were not big enough to carry everyone, and the supplies Wilkins wanted, across the Endicott Mountains to Barrow.

This is where Wilkins came up with his idea. He had the fuselage of the single engine Fokker, which was a plane that had already made the flight to Barrow several times. And he had the Fokker with the similar fuselage, which had been damaged in a crash, but with the larger wing that supported the extra motors. Wilkins idea was to remove the wing motors from larger Fokker, then take the wing off and put it on the fuselage of the Fokker with the inline six-cylinder water cooled engine.

The photographs of the 1927 ‘composite’ or ‘hybrid’ show a number of interesting things. Clearly it has the fuselage of the single engine Alaskan, with the inline water cooled engine. To change the name of the expedition from the Detroit Arctic Expedition to the Detroit News Expedition, Wilkins simply painted over the word Arctic, replacing it with the word News. And the hybrid used skis, not wheels. On some photographs of the hybrid you can see the mounting points under the wing – two at the front and one at the rear – where Anthony Fokker had slung the Wright Whirlwind motors.

But unfortunately, Wilkins had no more luck with this composite Fokker than he did the previous year. Attempting to take off at Fairbanks, the heavy metal skis did not slide easily, and the plane ended upside down. So the composite plane never actually left the ground. Wilkins abandoned plans to use it to fly his crew and supplies to Barrow.

He did however, take a reduced crew – two pilots, a radio operator and himself – to Barrow in the Stinsons. He left one plane, one pilot and the radio operator at Barrow, while he and pilot Ben Eielson flew north, over the Arctic ice. Eielson and Wilkins landed on the ice a number of times and took depth soundings, discovering that the Arctic was a deep ocean. After suffering engine trouble they abandoned the Stinson biplane and spent a week walking over the ice, back to Alaska.

The following year (1928), Wilkins wanted to try again, and he saw a new lighter plane – a Lockheed Vega. He immediately ordered one. To pay for the Lockheed Vega, he needed to sell something. He removed the large wing from the composite plane and put it back on the three engine fuselage, and offered it to Kingsford Smith without engines. Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm purchased new engines and that is the plane that became the Southern Cross. It was the original Fokker F VII fuselage and original three engine wing that became the Southern Cross. Kingsford Smith’s Southern Cross was not, as some people still claim today, a hybrid.

After the sale to Kingsford Smith, Sir Hubert Wilkins was still left with the fuselage of the single engine Fokker, while the damaged wing had been discarded. After pilot Ben Eielson died in a plane crash in 1929, Wilkins donated the fuselage to his family. Today the fuselage of the single engine Fokker is on display at the Hatton Eielson Museum, in North Dakota. The 1927 expedition name, where the word News has been painted over the word Arctic can still be seen on the side.

Sir Hubert Wilkins was in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1934, when he met Sir Charles Kingsford Smith and the pair had their photograph taken together. That photograph also appears in The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins.

Today, the Southern Cross is preserved in a hangar near the Brisbane Airport.