Recent biographies have seen Sir Hubert Wilkins receive plenty of media attention. There was even a stage play performed about Sir Hubert Wilkins at the Adelaide Fringe Festival. Unfortunately, much of what is being said about Wilkins continues to be inaccurate, and includes events that never happened.

To understand why there is still so much confusion about what Sir Hubert Wilkins actually did, and when he did it, it is necessary to go back through his life and examine the sequence of events that led to the fictional accounts of his life being published. And how those fictional accounts continue to be published today. Firstly, as revealed in The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins for the first time, Wilkins was involved in a suicide pact that went wrong, in Adelaide in 1908. After his health had recovered he stowed away on a ship to Sydney, where he worked as a theatre manager and cinematographer for two and a half years. In February 1912, he boarded a passenger ship and sailed directly to England, without returning to Adelaide. But after he became famous in 1928, he did not want the world to know what happened in Adelaide, so he covered his tracks, by changing the times he left Adelaide, and what he did after he left. In one inaccurate account he joined the carnival in Adelaide in 1905, travelled to Sydney in 1907, returned to Adelaide in 1908, and then went back to Sydney before sailing for England. We have to assume he has changed the dates, to hide the details of what happened in Adelaide.

But obviously Wilkins could not change the dates of well-known historical events. Six months after he arrived in England (in April 1912) he was sent by Gaumont to film and photograph the war in the Balkans. That was a date he could not alter. So, to cover the three-year gap in his story he wrote: “For about three years I toured the British Isles, Europe, Canada, and the United States on special assignments, photographing the 1909 revolution in Spain, German military manoeuvres, English military manoeuvres, a trip through Ireland, a trip across Canada, and so on.”

But of course, he did not do these things. But this started a pattern of Sir Hubert Wilkins adding fictitious events to the accounts of his life that he was called upon to write. In actual fact, he ended up writing four book-length autobiographies, and each had varying amounts of fiction and semi-fiction. Often he took events that happened, and embellished them. After he and Ben Eielson landed on the ice in the Arctic in 1927, and they had to abandon their plane and walk back to land, Wilkins wrote different accounts of falling through the ice. In an early account, he said he fell through the ice, but put his arms out to stop going all the way through and was wet up to the waist. In later accounts he had himself falling all the way through, opening his eyes underwater, and looking up to see the underside of the ice. This, he claimed, allowed him to realise it would be possible to travel under the ice in a submarine.

In 1942, Sir Hubert Wilkins had returned to America after a fact-finding tour of South East Asia, and was making his living on the lecture tour. He would travel to cities, mostly on the eastern seaboard, and stand up and speak in front of a paying audience. We know from correspondence with his booking agent, that the tours were not going well, and he was struggling to make a lot of money. His friend, Harold Sherman, who worked in radio, suggested Wilkins put up a proposal in which he could talk about his adventures to a radio audience. But of course, the adventures would need to be exciting to captivate the people listening.

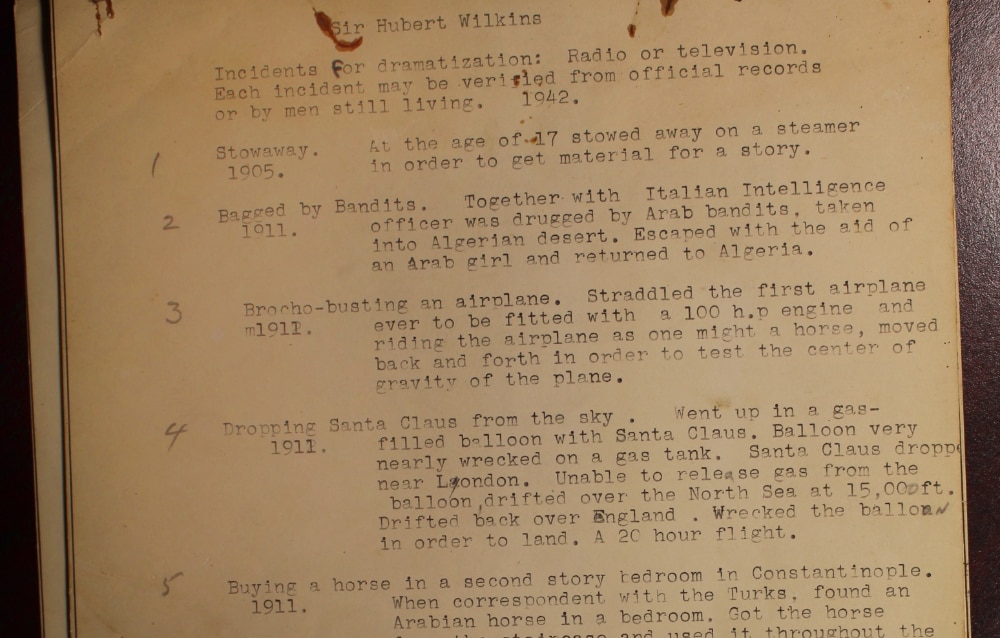

Wilkins started writing proposed episodes. Across the top he wrote: “Incidents for dramatization: Radio or Television. Each incident may be verified from official records or by men still living. 1942”.

The reference to television does not necessarily mean he intended to act out the episodes. In 1942, television in America was still broadcasting radio programs, as well as pictures.

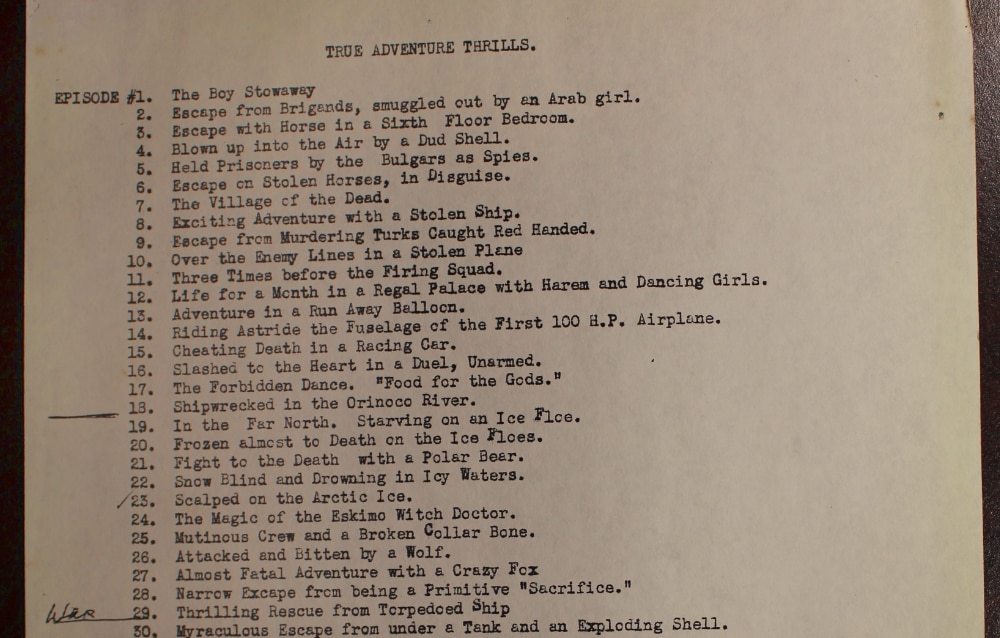

The second episode of the unnamed series is titled ‘Bagged by Bandits’, and is a fictitious account of being captured by slave traders when he stopped at Algiers in 1912. Wilkins’ radio drama failed to attract a buyer, so he tried again. The second time he called his series ‘True Adventure Thrills’, and he really sold his story with lots of exciting episodes, such as ‘Three Times before the Firing Squad’, or ‘Life for a Month in a Regal Palace with Harem and Dancing Girls’, and ‘Fight to the Death with a Polar Bear’.

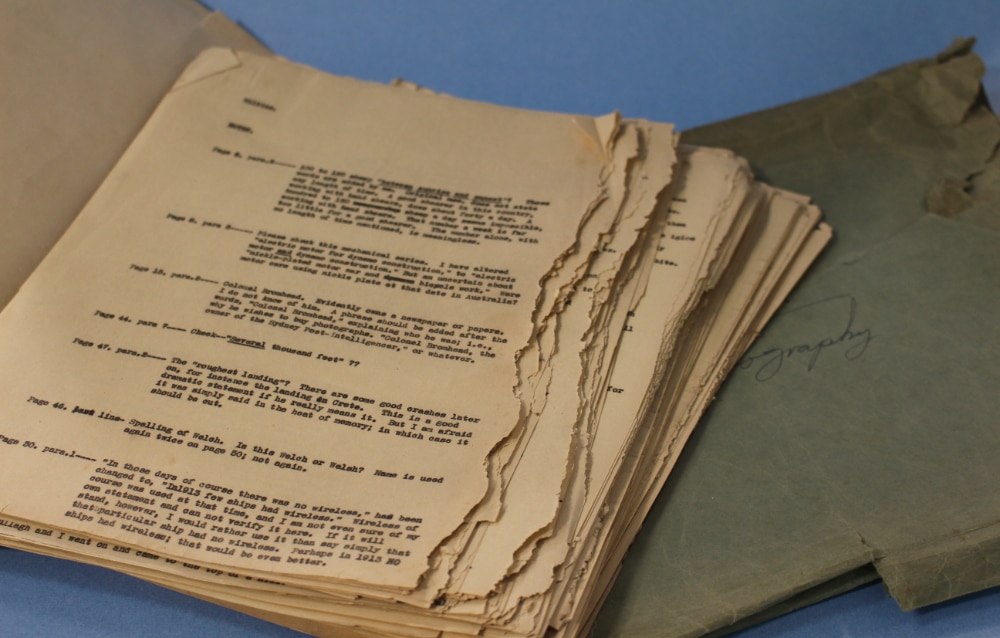

Wilkins typed up ‘True Adventure Thrills‘ in the same manner that one would type an autobiography. And here’s where it gets tricky. As I explain in the prologue of The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, his papers were mixed up and not archived in any order. I found chapters from different manuscripts in different private collections as well as at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at the Ohio State University.

But ‘True Adventure Thrills‘, pretty much stayed in one piece, and after Wilkins died in 1958, his first biographer, Lowell Thomas, published this semi-fictitious account of Wilkins’ life with only minor changes. It was published in 1960 as ‘Sir Hubert Wilkins: His World of Adventure‘ as told to Lowell Thomas. It has been republished many times and still remains a reference for people writing about Wilkins today. In his recent book ‘The Incredible Life of Hubert Wilkins‘, Australia’s most popular non-fiction author Peter Fitzsimons, quotes from Lowell Thomas (effectively quoting from True Adventure Thrills) more than 200 times.

How much is true? How much is exaggeration? How much is just outright fiction? It is difficult to tell. Burrowing down to find out what actually happened in the life of Sir Hubert Wilkins is still ongoing work. Since the publication of The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins I have received many emails from people asking why I did not include certain events, such as the time Wilkins supposedly met the Russian revolutionary Lenin. Or the time he warned the American about the attack on Pearl Harbor. The answer is simple. We have no proof those events happened. And more than ever the old adage that ‘pictures don’t lie’ should be remembered. We’ll know that Wilkins met Lenin when we find a photograph of the two of them together. Not before.

That is why people who have read The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins and, importantly, examined the photographs, many of which are published for the first time, are so amazed. Many people have said they have read all the previous biographies and books about Wilkins, but The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins reveals a completely different person. Yes. It does. And it proves another adage: ‘truth is stranger than fiction’.