Sir Hubert Wilkins has always been described as a fearless adventurer.

Recent biographies portray him as a man on a quest to help humanity by exploring the polar regions. His motivation, according to some people, was that he was trying to develop the science of long-range weather forecasting, which would help farmers produce bountiful crops and thereby reduce the devastating effects of droughts. It is a myth that Hubert Wilkins carefully cultivated and a story that simply isn’t true. Shortly after Wilkins died, his first biographer, Lowell Thomas, accepted Wilkins’ version of events and perpetuated the myth.

In producing The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, I have come to know Sir Hubert Wilkins as a deeply conflicted person, often filled with self-doubt, and always trying to reconcile his strict Protestant upbringing with his love of music, art, alcohol and women.

A real challenge in selecting the photographs and the extracts of letters and writings to include in The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, was deciding what story to tell. Wilkins certainly lived a life of incredible adventures, but there was also a side to him that he did not want people to see.

After he was knighted in 1928, and asked people to call him Sir Hubert Wilkins, rather than George Wilkins, he purposely set out to invent the story around his life. He did that to hide the truth of the tragic events that happened in Adelaide in 1908, and the real reason he left home, and why he never spoke to his father again.

When writing about Hubert Wilkins, the first challenge is to distinguish true events from the fiction that Wilkins carefully concocted, then maintained all his life. Going beyond the myth, to gain insights into his real motives, is difficult, but it is one of the reasons his photographs are so critical. At various times in his life, Wilkins was a polar explorer, a pioneer aviator, and Australia’s official photographer in World War I. When you add the two years he spent in the Australian Outback, his time in the early Australian cinematography industry, his work for the US government during World War II, his travels in Russia, and his Arctic submarine expedition, then he obviously had a rich and varied life. It is hard to see the thread, or the motivation that is consistent in his life, and this made it very easy for Wilkins to create a false story to misdirect people and why, seventy years after his death, he is still an enigma.

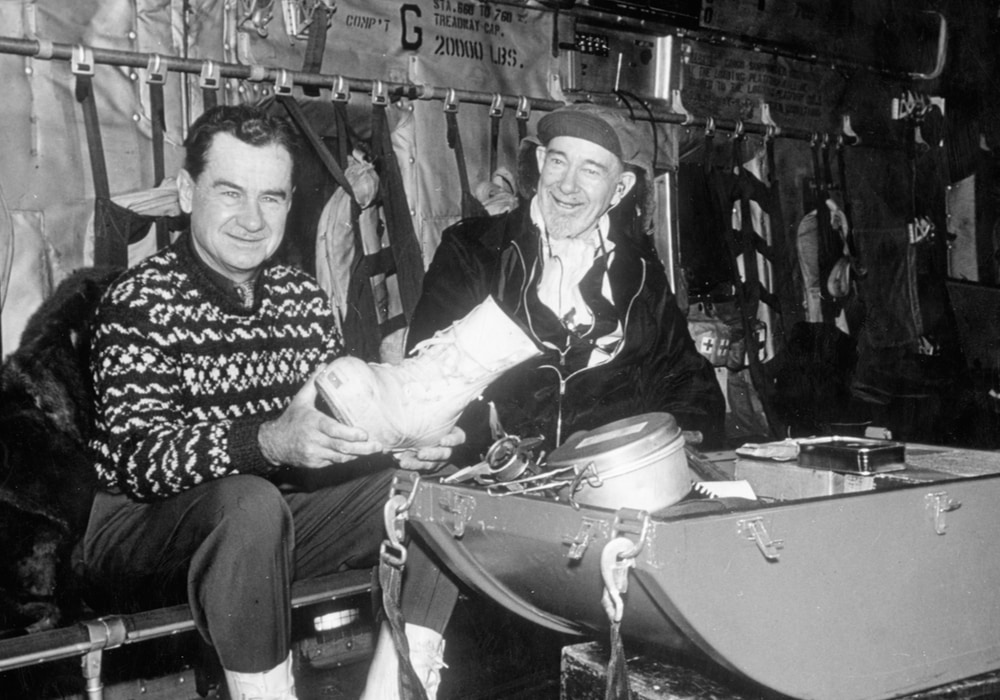

But whatever Hubert Wilkins was doing in his life, he always carried a camera. He photographed everything and kept everything. At the time of his death there were thousands of photographs in his enormous collection. So while he could easily change his story to conceal what happened when he wrote about his life, he could not change the photographs.

In writing and compiling The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, I immediately became aware that the book was so much more than just a visual record of Wilkins and his adventures. It is really a revealing documentary about Hubert Wilkins’ life told in book form. I knew when I commenced the project that much of what Wilkins wrote was fiction, but there were many stories I was unable to validate or dismiss with certainty. Stories about being captured by slave traders on his first trip to England, or being put in front of firing squads when he covered the Balkans War in 1912, I knew were fiction. So was the story of meeting and interviewing Vladimir Lenin, when Wilkins was in Russia in 1922. Wilkins said that it happened, but it never did. He explained exactly what happened in letters, written from Russia at the time, to his mother. Those letters have remained in a private collection ever since. What is interesting also is that Wilkins does not mention meeting Joseph Stalin, when he went to Russia in 1938. He attempted to get Stalin to give him a submarine to explore the Arctic. Later, when recalling events, Wilkins doesn’t talk about the Russian dictator, but again the photographs tell a different story.

There were many other stories, about which I was uncertain, but photographs provided the answers. Wilkins talks about he and his wife, Suzanne, remaining childless all their lives. But finding photographs of both Wilkins and Suzanne with their daughter, proves that to be false. Wilkins talks about the beautiful young artist who attempted to stow away on one of his planes in 1926, when he was flying in the Arctic, then going dancing with the woman later that evening. At first that sounded like a typical Wilkins’ fictional story, but I realised it was true when I found the photographs.

All this comes back to the question of why Hubert Wilkins was so intent on creating a myth around his life. The real, and provable adventures that he had are so remarkable that it seems incredible that he would want to embellish them, or make others up. The answer lies in Sir Hubert Wilkins’ true motives for setting out on his life journey. When he picked up a camera and strode onto the world stage, he began a unique journey that is only now coming to be appreciated.

The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, tells that story through previously unpublished writings and photographs, and proves the old adage that photographs don’t lie.