In the basement of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, in a special area where both humidity and temperature are carefully controlled, is the greatest collection of World War I photographs in the world. The collection, which includes thousands of photographs from the Western Front, Gallipoli, and the Middle East, far surpasses any other collection of World War I photographs—even those held at the Imperial War Museum in London—for three reasons.

Firstly, no other collection has so many photographs. In the Australian War Memorial there are thousands, which record all the battlefields, details, and fighting of the war. There is not another collection of photographs that comes near to covering so many subjects in such detail.

Secondly, the quality of the photographs at the Australian War Memorial are superior to anything else. Most of the official photographs have been shot on large format, full- and half-plate glass negatives, rather than on smaller format roll film negatives.

Thirdly, the official photographs are usually accompanied by detailed information, saying specifically where they were taken, and often include the names and ranks of the people in the photographs. Sometimes the names of more than 150 people are recorded in a single photograph.

A century after the end of World War I, that such a photographic record and database exists in Australia is astonishing. And it exists because of the vision, sacrifice and hard work of two men: official Australian war historian Charles Bean, and official Australian war photographer George Hubert Wilkins.

The story of Charles Bean has been told many times, and his work as Australia’s official World War One historian—both during the war and the twenty years after it that he spent writing and editing Australia’s official history—has been told, celebrated and honoured. Everyone acknowledges Charles Bean as the driving force behind the establishment of the Australia War Memorial.

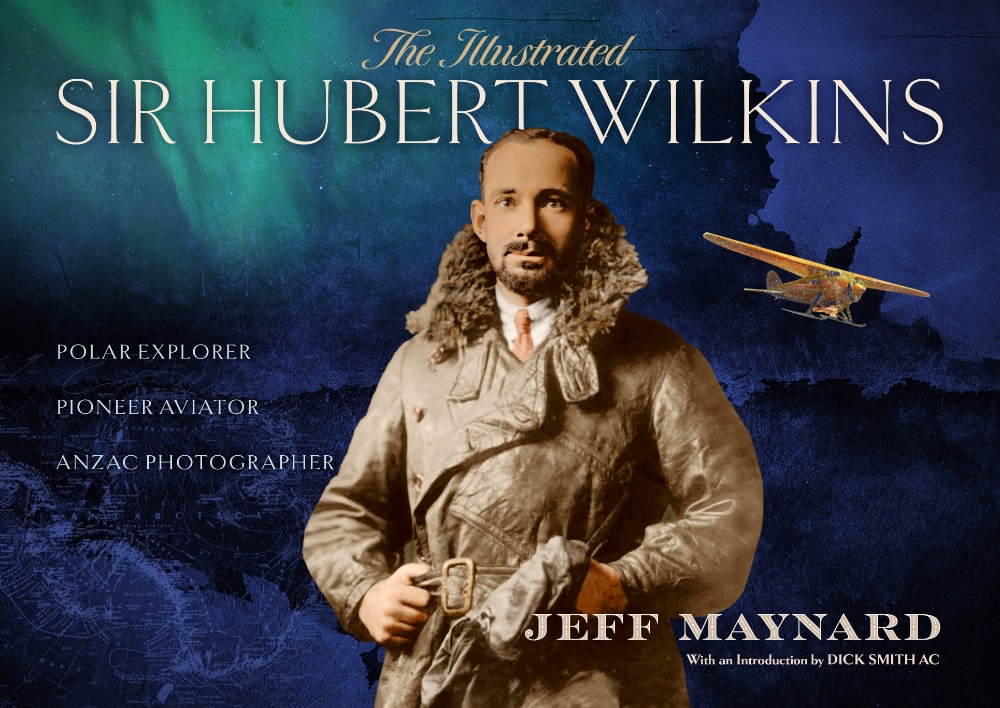

But the role played in producing this unique collection of photographs by pioneer aviator and polar explorer George Hubert Wilkins (later Sir Hubert) is virtually unknown. I’m pleased to say that the publication of The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins has focussed more attention on the key role played by George Hubert Wilkins in recording Australia’s Anzac history, and the outstanding collection of World War One photographs held at the Australian War Memorial.

By way of background, Charles Bean had been arguing for almost a year for Australia to have its own official photographer at the Western Front so that he could record the war pictorially. Individuals were banned from carrying cameras. Eventually, George Hubert Wilkins and James Francis (Frank) Hurley were assigned to Bean. Wilkins and Hurley knew each other and were friends, having both recently returned from polar expeditions. They travelled from London to France on 17 August 1917, to be met by Charles Bean, then driven to the Western Front. While Frank Hurley’s task was to take ‘promotional photographs’ that could be used in newspapers to assure people in the United Kingdom and around the world that the war against Germany was being well run and was succeeding, Bean wanted Wilkins to compile a complete and accurate record of all aspects of the war.

That meant taking lots of photographs. Ultimately, in the fifteen months between when he arrived at the Western Front, and the Armistice on 11 November 1918, George Hubert Wilkins was responsible for approximately 4000 photographs. Shortly after arriving, Wilkins photographed the ground where the Anzacs had already fought battles, such as Pozieres and Bullecourt. Then he set out to photograph every place the Anzacs were living and fighting. As Charles Bean wrote in his diary, “I want a photograph of every trench, and every piece of ground over which the Anzacs have fought”.

To the modern reader, this may sound unnecessary—photographing barren battlegrounds—but Bean and Wilkins understood that to the Australian families of the men and women at the Western Front, such photographs were important. The war was being fought on the other side of the world, and people in Australia, especially in the early part of the 20th century, had little opportunity to visit France. Bean wanted a complete photographic record that could be taken to Australia for people to see. And all the photographs had to be carefully referenced. After the war, when prints of the thousands of photographs toured Australia, parents, wives, children, brothers and sisters, could go to an exhibition, nominate a battle and a date and, using the indexed referencing system, see where their loved ones had been. Bean recorded an instance of a mother in Melbourne breaking down and weeping when she was shown a photograph of the ground where her son had been killed.

Wilkins’ incredible work ethic, which he had demonstrated from the time he left South Australia in 1909, was ideally suited to the type of work that Charles Bean had in mind. While Frank Hurley, and photographers from other countries, wanted to take spectacular pictures they could use to promote their shows, Wilkins was willing to do the hard, unrewarding work necessary to get a complete and accurate record that people still refer to today.

The second reason why George Hubert Wilkins’ photographs of World War One and the Western Front are unique is the high quality of the photographic negatives. Wilkins almost exclusively used a full-plate or half-plate camera. That means that each negative for each photograph is a square glass plate, inserted in the camera one at a time. Roll film cameras were available, but their smaller negative would not have produced the high resolution of the larger glass negatives. Consequently, the photographs of the roll film cameras would not be able to be enlarged to the same extent. Important detail would have been lost. Or, more correctly, an important treasure trove of unseen detail would not be available to researchers, descendants and historians today.

Using these large format cameras created extra difficulties for the photographers. Full plate cameras needed a tripod because they were large and heavy. In an often-used photograph of Wilkins on a tank taking a photograph (the photograph is reproduced in The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins) Wilkins is shown using a Thornton Pickard full plate camera. While researching The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins, I sought one of these cameras and found an owner who showed me how to use it.

The process of taking a photograph is a two-person task, so the photographer needs to be accompanied by an assistant to help carry the tripod and the heavy box of glass negatives, as well as the camera. While being carried, the camera is folded down and kept in a canvas bag. Taking a single photograph means getting the camera out of the bag, unfolding it, setting up the tripod, looking through a special ground glass screen which drops down (while covered with a black cloth) to frame the photograph, then inserting a plate carrier which has been pre-loaded with a negative in a darkroom, removing the slide from the plate carrier, exposing the negative, then repeating the process in reverse order before another photograph can be taken.

A single photograph can take five minutes to capture, and Wilkins often did it while he was being shot at. But Charles Bean and George Hubert Wilkins must have understood that using glass plate cameras, as opposed to compact roll film cameras was worth the added work and risks to get the incredible detail that is unique to Australia’s collection of official World War I photographs.

The third factor that distinguishes the work of George Hubert Wilkins and Australia’s World War I photographs is the fact that they are accompanied by an almost unbelievable amount of details. In some photographs, 150 people have been photographed and all their names and ranks recorded, along with their position in the photograph. The work involved must have taken hours. But 100 years later the Australian War Memorial has able to set up a database of names, matched to the photographs, so descendants and others interested people can search the enormous database of thousands of names and photographs, to find a person from more than a century ago. No other collection of World War One photographs does that.

Again, it comes down to the work and dedication of George Hubert Wilkins. After the Armistice, Wilkins spent nine months in London (often revisiting the battlefields in France and Belgium) to prepare all the glass negatives and their accompanying notes, for shipping to Australia. Charles Bean was in Australia at the time, preparing for the return of the photographs and artefacts and trying to establish a permanent home for the material. During the nine months he spent cataloguing the photographs Wilkins worked with a team. He even took a photograph of them working at the Anzac Headquarters in Horseferry Road, London. The photograph shows shelves of boxes of glass plate negatives, and nine people working with indexing cards, notes and photographic prints.

Australia has a unique collection of World War I photographs. It is acknowledged by experts around the world as the most comprehensive, detailed and authoritative visual record of the First World War, anywhere in the world. It is unfortunate that, until recently, the man responsible for the photographs, the explorer and aviator George Hubert Wilkins, has not received the same recognition. That is why I, and the people responsible for Netfield Publishing, are particularly proud to be able to present the beautiful limited edition book The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins.